RC22. Conjuring Data in Lisp

Daily dispatches from my 12 weeks at the Recurse Center in Summer 2023

“Let me do something that I think is really going to terrify you.” Well, Professor Abelson, you weren’t wrong.

Elementary Data Structures in Lisp

Okay, so, stepping back. I recently advanced to Chapter 2 of SICP, and we’ve begun to explore implementing higher-level data structures using pairs.

For instance, if we want to be able to handle rational numbers, we can instantiate a rational number object by using cons to pair two numbers, n (a numerator) and d (a denominator), like this:

(define (make-rat n d) (cons n d))

Now we can create some accessor procedures using car and cdr that operate on rational number objects – numer returns the numerator of the rational number, and denom returns the denominator:

(define (numer p) (car p))

(define (denom p) (cdr p))

To make our lives easier, let’s also define a print-rat function, that pretty-prints a rational number object:

(define (print-rat p)

(newline)

(display (numer p))

(display "/")

(display (denom p))

(newline))

Here’s our code in action:

1 ]=> (define a (make-rat 5 8))

;Value: a

1 ]=> (print-rat a)

5/8

;Unspecified return value

Next, let’s create some methods to operate on rational numbers using the accessor procedures defined above. Here’s a refresher on rational number math:

\[\begin{align} \text{Addition }\frac{N_1}{D_1} + \frac{N_2}{D_2} & = \frac{N_1 \cdot D_2 + N_2 \cdot D_1}{D_1 \cdot D_2} \\ \\ \text{Subtraction }\frac{N_1}{D_1} - \frac{N_2}{D_2} & = \frac{N_1 \cdot D_2 - N_2 \cdot D_1}{D_1 \cdot D_2} \\ \\ \text{Multiplication }\frac{N_1}{D_1} \cdot \frac{N_2}{D_2} & = \frac{N_1 \cdot N_2}{D_1 \cdot D_2} \\ \\ \text{Division }\frac{\frac{N_1}{D_1}}{\frac{N_2}{D_2}} & = \frac{N_1 \cdot D_2}{N_2 \cdot D_1} \end{align}\]Implemeting this in Scheme (without automated reducing of fractions) would look like this:

(define (add-rat x y)

(make-rat (+ (* (numer x)

(denom y))

(* (numer y)

(denom x)))

(* (denom x)

(denom y))))

(define (sub-rat x y)

(make-rat (- (* (numer x)

(denom y))

(* (numer y)

(denom x)))

(* (denom x)

(denom y))))

(define (mul-rat x y)

(make-rat (* (numer x)

(numer y))

(* (denom x)

(denom y))))

(define (div-rat x y)

(make-rat (* (numer x)

(denom y))

(* (denom x)

(numer y))))

So if we make a few rational numbers …

1 ]=> (define a (make-rat 5 8))

;Value: a

1 ]=> (print-rat a)

5/8

;Unspecified return value

1 ]=> (define b (make-rat 1 3))

;Value: b

1 ]=> (print-rat b)

1/3

;Unspecified return value

… we can operate on them using our new rational number methods:

1 ]=> (print-rat (add-rat a b))

23/24

;Unspecified return value

1 ]=> (print-rat (mul-rat a b))

5/24

;Unspecified return value

1 ]=> (print-rat (sub-rat a b))

7/24

;Unspecified return value

1 ]=> (print-rat (div-rat a b))

15/8

;Unspecified return value

A Closer Look at Pairs

At its core, the rational number data structure implemented above, as well as all the procedures that manipulate and combine those objects, rely upon Lisp pairs:

(define p (cons x y))instantiates pairpcomprising of termsxandy(car p)returns the first item (x) of pairp(cdr p)returns the second item (y) of pairp

We’ve been treating these pair procedures and types as primitive in Lisp, taking for granted that they work and do what we expect. Which in and of itself is a useful habit to get into, since it encourages the kind of “wishful thinking” Abelson and Sussman often allude to – that we utilize procedures we haven’t yet written and assume they work so that we can compartmentalize our thinking and focus higher-order problems. And as for those other, lower-level procedures that don’t actually yet exist? We can tackle those later, and in turn the structures on which they may rely.

But, Professor Abelson asks, what if we wanted to conceptualize and build the infrastructure required for pairs ourselves? How would we approach the problem of implementing the thing on which we’ve been relying (rightfully) this whole time?

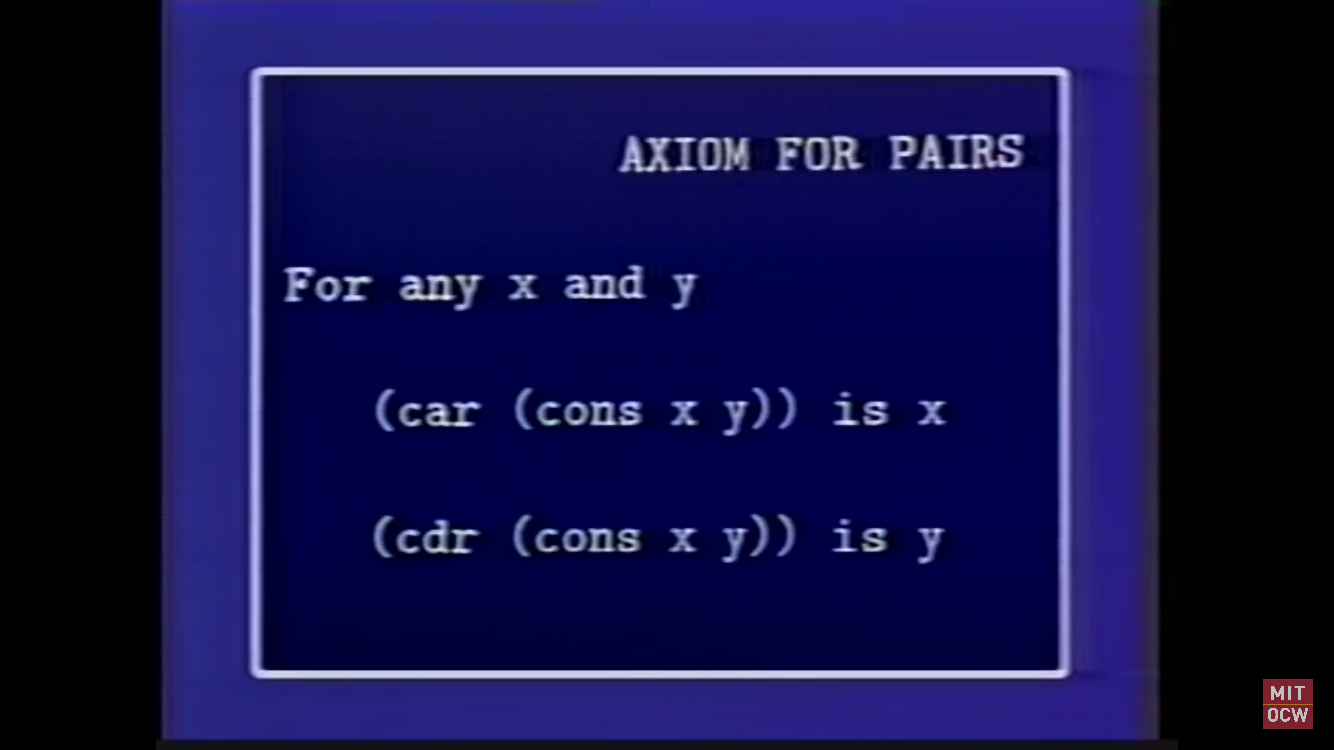

The only real requirement, he points out, is that such a procedure satisfy the following axiom:

(car (cons x y)) => x(cdr (cons x y)) => y

So how exactly do we do that?

“What you’re going to see,” teach says, “is that pairs can be built from nothing at all.” We’ve been warned.

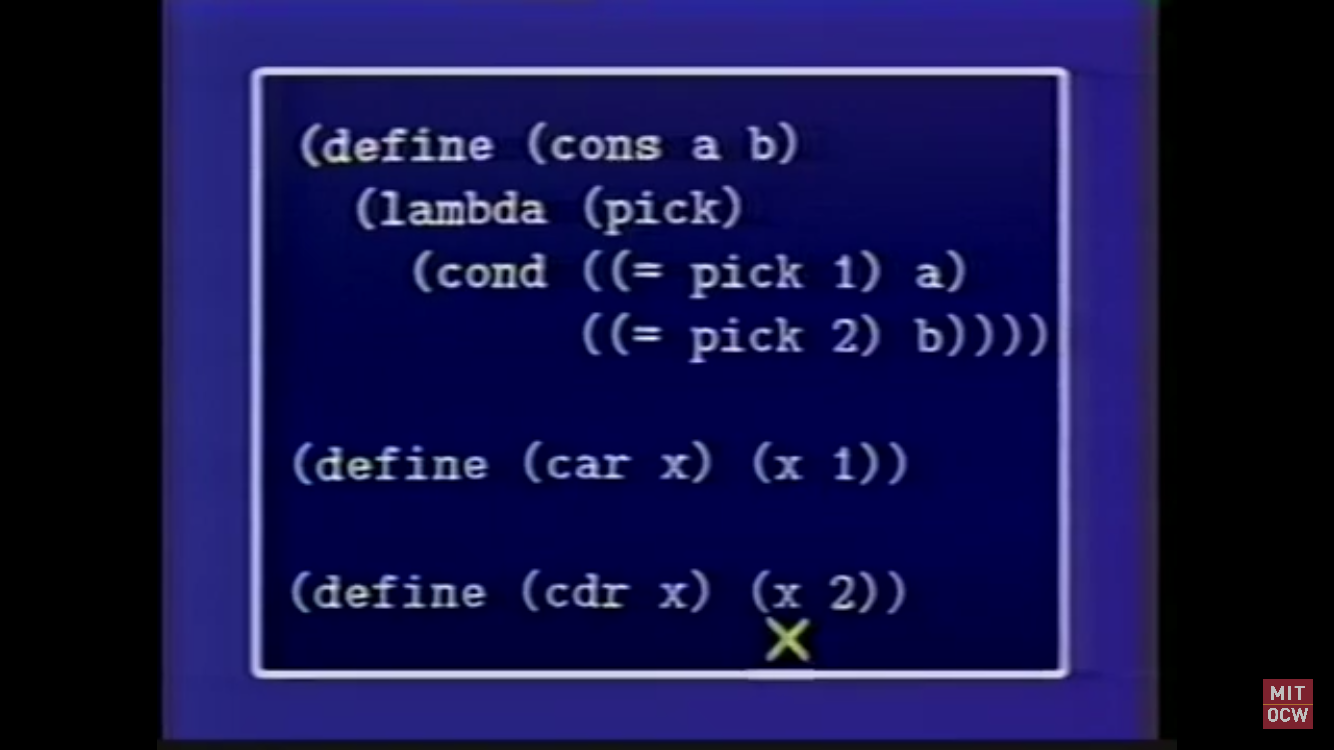

Here’s the implementation of cons, car, and cdr that satisfy the axiom above:

(define (cons a b)

(lambda (pick)

(cond ((= pick 1) a)

((= pick 2) b))))

(define (car x) (x 1))

(define (cdr x) (x 2))

Well, Prof. was right: I’m scared. Because cons is not returning a piece of data, as expected; it’s returning a procedure – a procedure that, once we wrap our minds around it, is now defined in terms of its arguments a and b.

Pair Sorcery

Let’s take a closer look at this. Say we want to define p as the pair of 5 and 9:

(define p (cons 5 9))

What we might expect is for p to be something like a tuple in Python, or a two-element list: two values, 5 and 9, yoked together into a unit. Of course that’s what we’re trying to build, and we can’t exactly rely on the thing that we’re in the process of building in order to build it. That’s why this implementation of cons is actually returning a procedure.

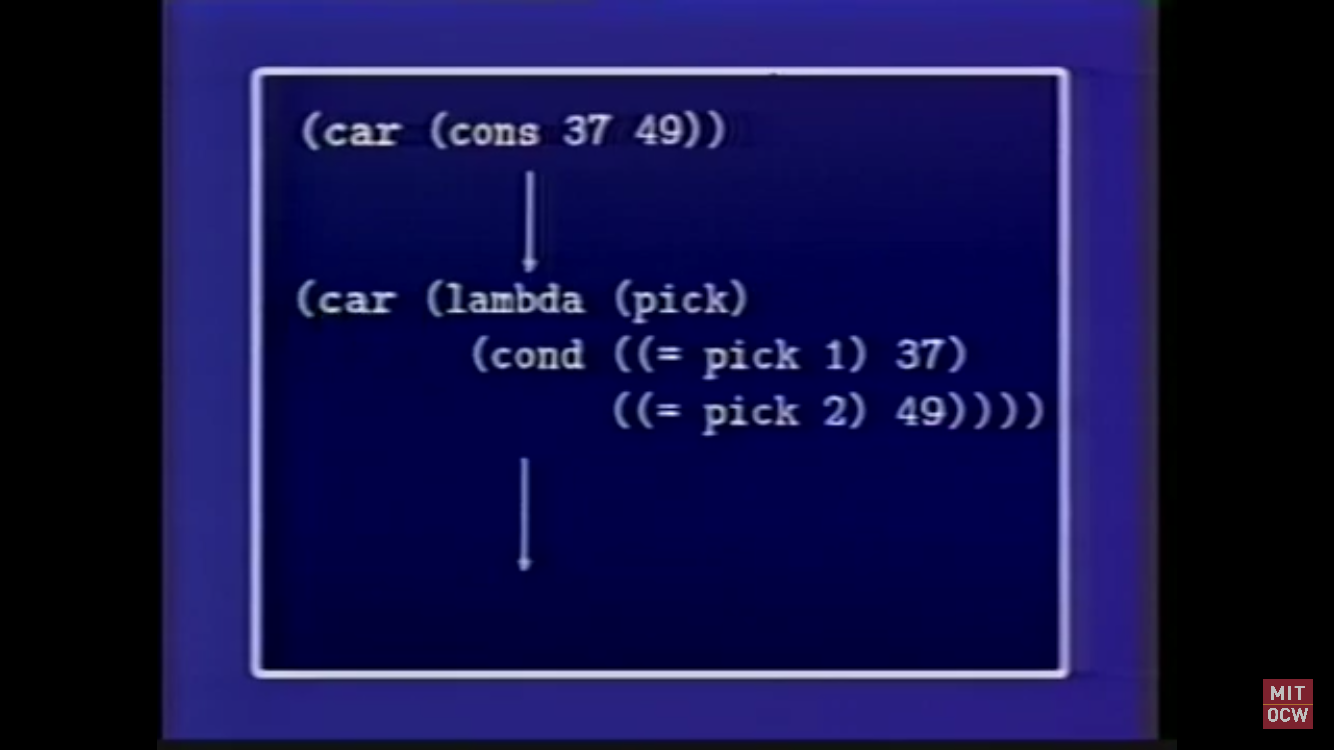

When we call define p (cons 5 9)), then, its equivalent, by substitution, is this:

(define p

(lambda (pick)

(cond ((= pick 1) 5)

((= pick 2) 9))))

p, in other words, is a procedure that takes a single parameter, pick, which returns 5 if pick == 1 else 9 if pick == 2. When we call (car p), then, what’s happening (again, by substitution) is this:

(car p)

returns

(p 1)

which expands (roughly) to

(p (lambda (1)

(cond ((= 1 1) 5)

((= 1 2) 9))))

Now we can see that if we call (car p) where p has been instantiated as a pair of 5 and 9, car is returning procedure p and the formal argument 1, as a result of which p returns 5 conditionally.

Final thoughts

The SICP profs often talk about how the line between data and procedures begins to blur at a certain point, and, well, we are reaching that point. Intuitively, a structure like a pair – two values that are coupled somehow – seems like it ought to be a data structure (and actually it may very well be under the hood, I’m not sure). But in this implementation anyway that data structure is ethereal, since the only thing there in the end is an incantation.

Other goings-on of the day

- made it to checkins for the first time in a while

- worked on a particularly long blog entry since I wanted to memorialize yesterday’s wins

- worked a bit on K&R

- had some great coffee chats with folks whom I hadn’t really met or talked with much yet

- nand2tetris group meeting, where we shared our assembly code for blacking out and clearing a screen