RC15. Memories… you’re talking about random access memories…

Daily dispatches from my 12 weeks at the Recurse Center in Summer 2023

This week my simulated computer is starting to take shape thanks to some RAM units and a Program Counter.

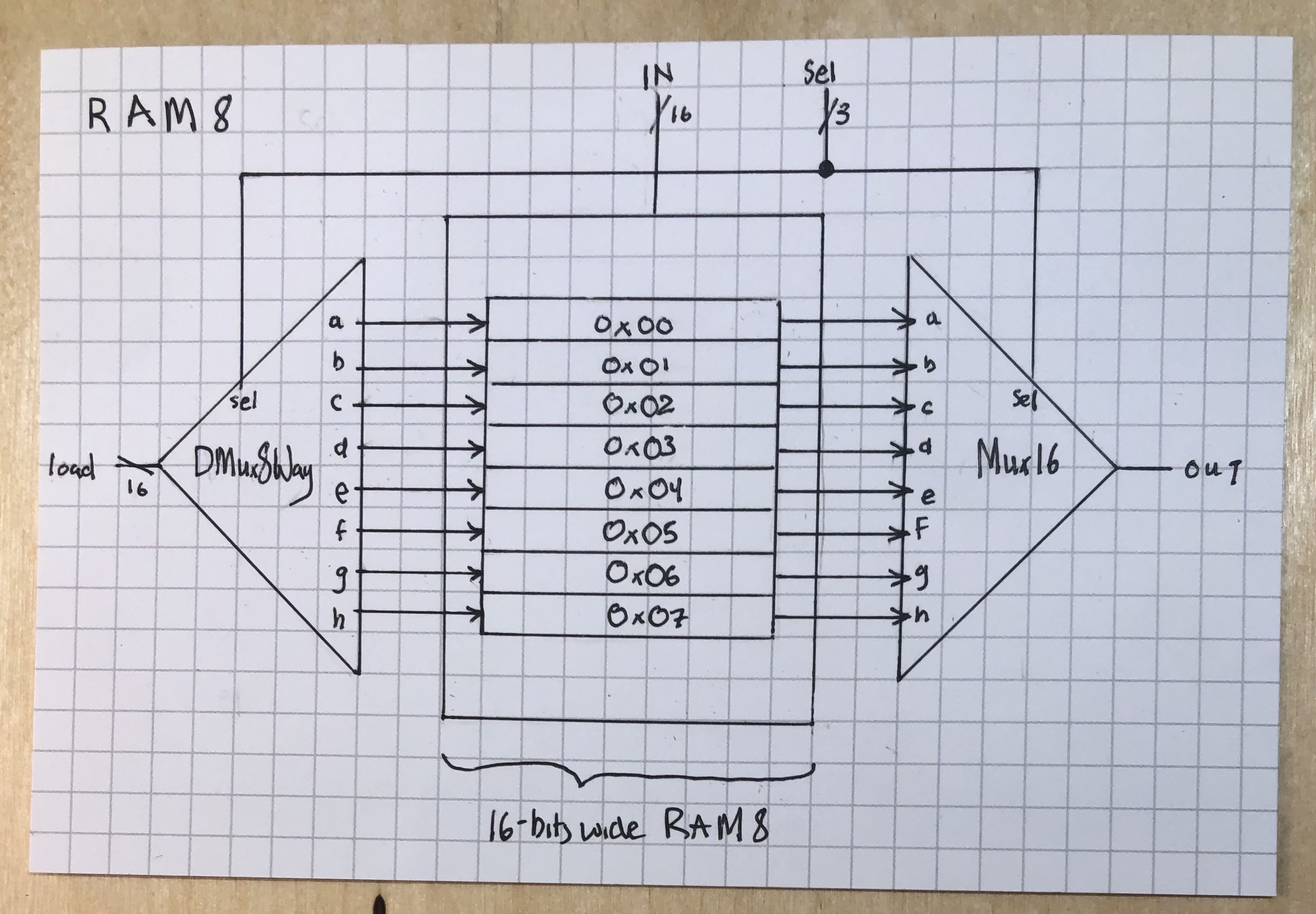

Here’s a quick run-through of building a RAM of size 8, meaning that it has 8 separate addresses to store (in this case) a 16-bit (or 2-byte) value.

DMux redux

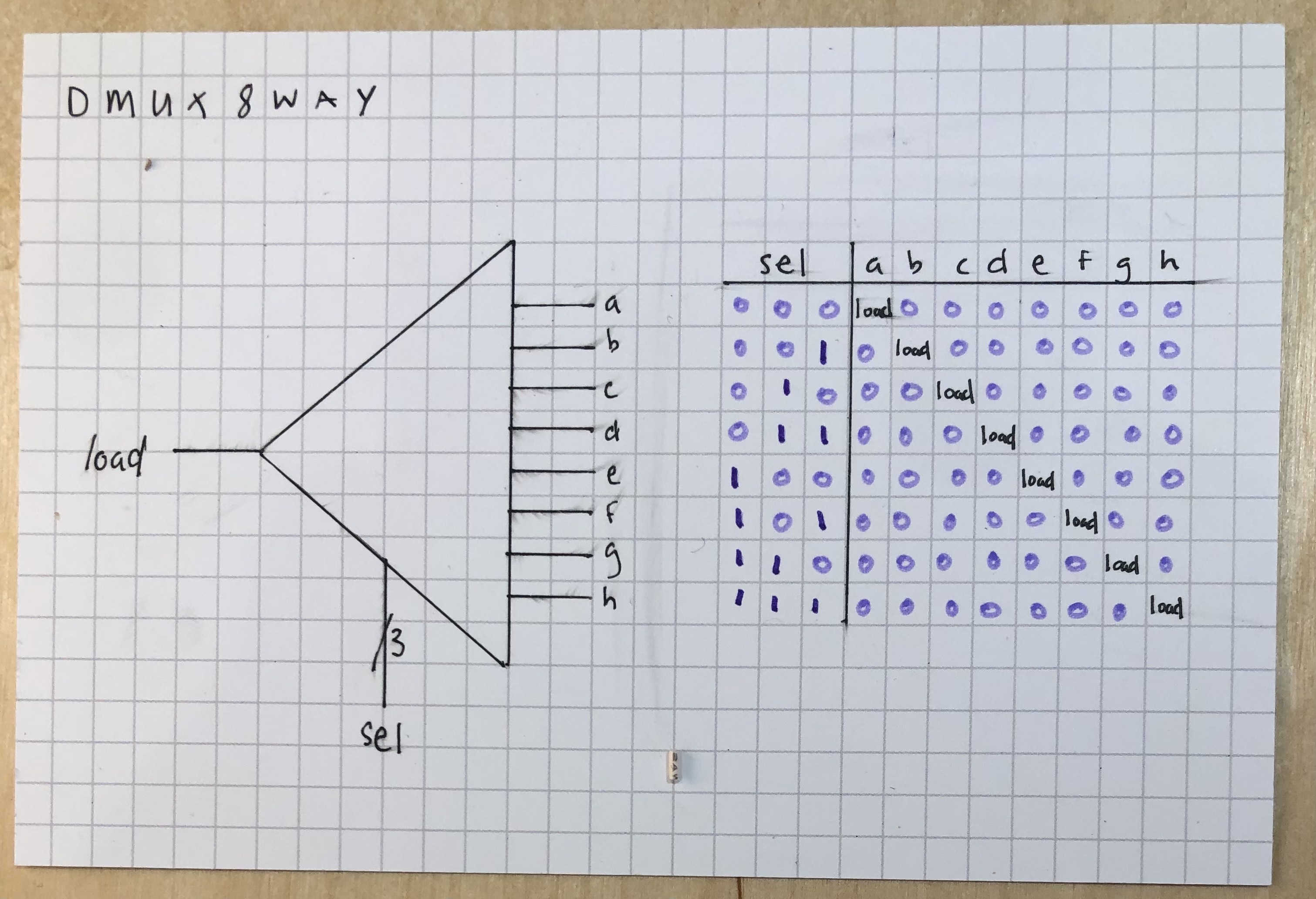

A DMux is a demultiplexer. A demultiplexor uses a selection bit or bits (sel) to select which output will carry the value of the load bit. A basic demultiplexor would have two outputs, a and b. If the sel bit is 0, then a = load (and b = 0); if the sel bit is 1, then b = load (and a = 0).

The above 8-way demultiplexor is a bit more complicated, but it’s the same idea. The only difference is that, instead of having just two outputs that can be selected to carry the load signal (a and b), it has eight: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, and h. In order to access eight separate outputs, though, the sel input is no longer a single bit but three bits, since three bits can be permuted in 8 different ways (\(2^3 = 8\)).

This DMux8Way is going to be the component in our RAM that tells us which of eight memory addresses we want to load into. (And it’s eight because, again, the demultiplexor allows us to use its three sel bits to choose which of its 8 outputs will carry the load signal).

Mux redux

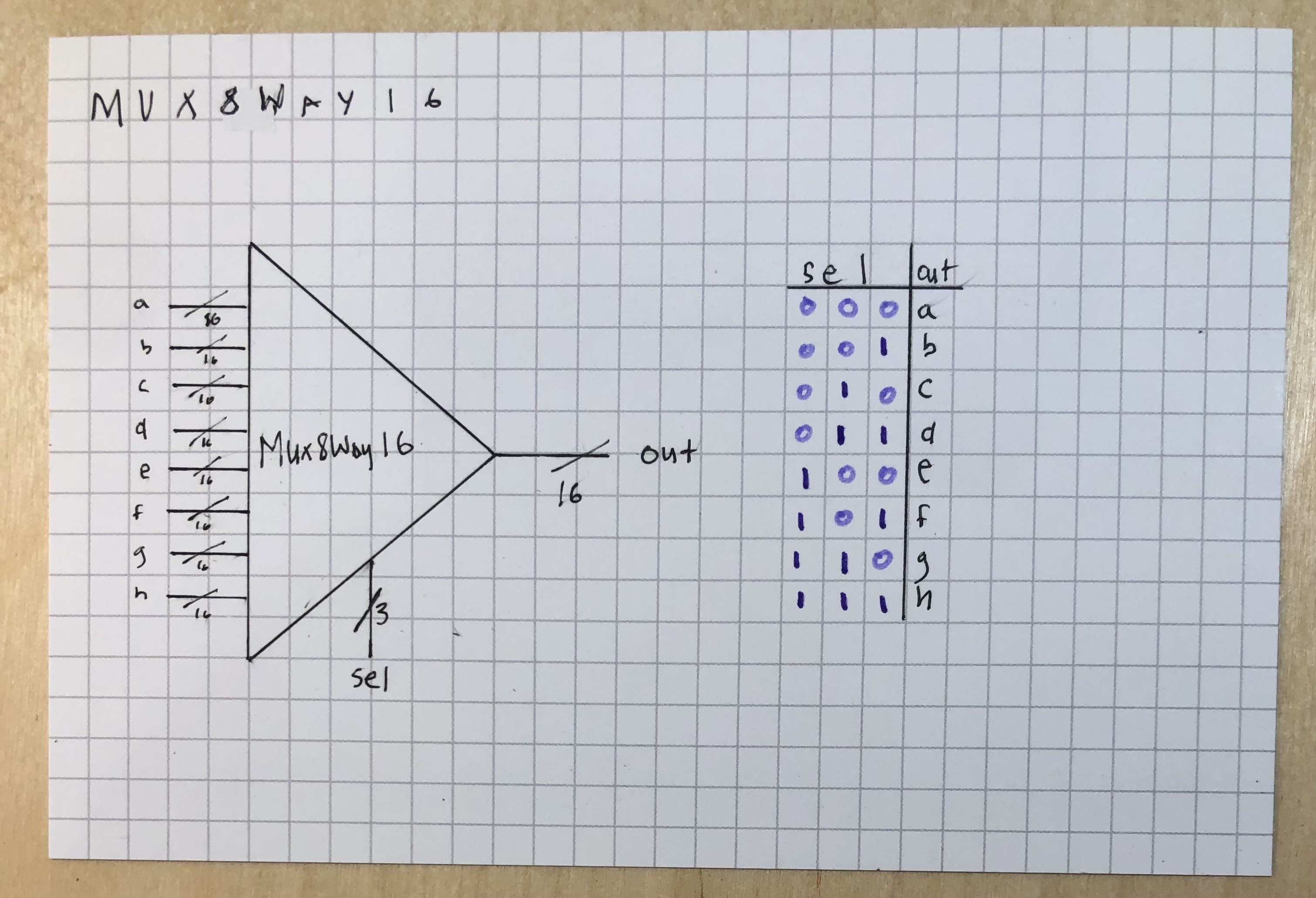

A Mux is….. a multiplexor! It’s the opposite of a DMux, more or less: in the most basic case, there are two inputs, a and b, which are output to out according to the sel select bit. If sel == 0, then out = a; if sel == 1, then out = b.

Here, we have a Mux8Way16. The 8 refers to the 8 inputs we have to choose from (a, b, c, d, e, f, g, and h). The 16, on the other hand, refers to the fact that each of those inputs is 16-bits wide. As with the DMux8Way, we need three select bits because we have 8 outputs.

In our 8-unit RAM, this Mux8Way16 is going to be what allows us to access each of those 8 addresses and output them.

Making the RAM

Time to build the memory unit. Because the Mux and DMux can each accomodate 8 addresses, we’re going to need 8 16-bit registers, one for each address. Each register takes a 16-bit input, which it loads when load is set to one. And at all times the register outputs whatever it’s storing. So what we need is a way to control which register to load in into or which register to read from at any given moment, which is where the Mux and DMux comes in:

Errata: Mux16 should be Mux8Way16;

Errata: Mux16 should be Mux8Way16; load input to DMux8Way is 1 bit, not 16-bit; and out output from Mux8Way16 (erroneously Mux16 above) is 16 bits wide.

The entire RAM unit has three inputs:

- the 16-bit wide

in: this is the value that we want to potentially store somewhere in memory - a 3-bit address

sel: this specifies the memory address we want to write to or read from - the

loadbit: when this is 1, we’ll writeinto the address specified bysel; when it’s 0 we do nothing

What’s cool is that now we can start clustering 8-unit RAMs together using the same Mux/DMux method. With another DMux8Way and another Mux8Way16 (and 6 select bits rather than 3), we can chain 8 of these RAMs together to create a 16-bit RAM with 64 addresses. With another Mux/DMux (and 9 select bits) we can cluster 8 RAM64s together to get a RAM with 512 addresses. 8 RAM512s can be linked using another Mux/DMux to build a memory with 4096 addresses. Etc. etc.

Also

This Weekend I

- paired with some RC folks on CPL exercises

- gave Part I of my presentation on heaps to some folks from a meetup group I go to

Today I

- worked on BYOL, before and during weekly BYOL meeting

- went to a roundtable for and by career switchers

- paired with some nand2tetris folks on the stuff featured in this very blog

- had some coffee chats